Users of early elevators were responsible for opening and closing the doors manually, and sometimes the doors were left open, creating a hazardous situation with the shaft exposed. As Andreas Bernard writes in his 2006 history of elevators:

. . .in the 1880s, manually operated or hinged doors. . .on each floor still frequently misled careless passengers wishing to enter the cab into opening them and falling into the shaft. (Andreas Barnard, Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator, p.31)

Duluthian Alexander Miles helped solve this problem by inventing an improved mechanism for opening and closing elevator doors when the car arrives at or departs the floor. This is just one accomplishment of this successful and creative businessman who lived in Duluth in the late 1800s and was thought at the time to be the wealthiest black man in the Midwest.

Winona Daily Republican Aug.8,1866

Alexander Miles was born in Pickaway County, Ohio, probably in January of 1837. His father was Michael Miles and his mother was Mary Pompy. He grew up in Ohio, but in the late 1850s moved to Waukesha, Wisconsin, where he made his living as a barber. By June of 1863, according to Civil War Draft Registration records, Miles had relocated to Winona, Minnesota, where he also worked as a barber. In July of 1864 he purchased the OK Barber Shop in Winona. He also developed and manufactured a new hair care product called

Tunisian Hair Dressing, which he claimed was “for cleansing and beautifying the hair, arresting its falling off, and imparting to it a healthy and natural tone and color.”

In Winona he also met Candace Dunlap, a married woman who had a millinery shop in town. Candace, a white woman, was born in New York in 1834 and grew up in Indiana. She was married to Samuel Dunlap in 1853 and they moved to Winona a couple of years later where he worked as a grocer. By 1860 they had two children, a daughter Alice and a son Laommi. Soon, Candace and Alice were living with Miles in Winona, and Samuel and Laommi had moved to Indiana where Laommi was living with Candace’s mother Miranda.

Sometime after June of 1870 and before December of 1871, Miles and Candace moved to Toledo, Ohio, where he continued to work as a barber. In Ohio, he received his first patent, which was for “Improvements in Compounds for Cleansing the Hair.” He called the compound Cleansing Balm.

By May of 1875, Miles and Candace, along with Alice, had moved to Duluth. It was a time when Duluth was undergoing rapid growth—the Lake Superior & Mississippi Railroad had just started passenger service to the city in 1870, and Duluth was beginning its recovery from the Panic of 1873 and on the verge of rapid growth. As he said near the end of his life, Miles had seen great possibilities for Duluth in the 1870s:

. . . I was in search of a place with which I could grow up. There were two or three other places at that time attracting attention, Kansas City and St. Louis being very prominent, but it seemed to me that Duluth had the best prospects of all and would one day be a great city at the head of Lake Superior. (Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 3, 1907, p.35)

During the approximately 25 years Miles lived in Duluth, the city’s population grew from 2,200 (1878) to 52,969 (1900). Candace gave birth to the couple’s only child, Grace, in Duluth on April 9, 1876.

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Miles operated a very successful barber shop on Superior Street in downtown Duluth. In 1882, the Duluth Daily Tribune described the shop:

Alexander Miles, Duluth’s popular barber and hair-dresser, has just employed another first-class barber and put in still another barber’s chair in his “tony” shop, and he now has therein five of those patent elevated-seated chairs, which are capable of adjustment as desired, and each one of which is a complete child’s hair-cutting chair. (Duluth Daily Tribune, June 15, 1882, p.4)

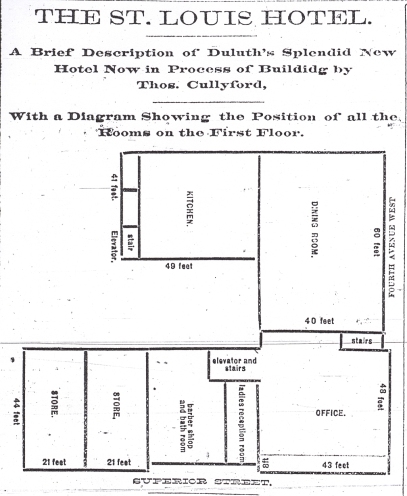

Later in that year, when Thomas Cullyford opened the St. Louis Hotel on the southeast corner of Fourth Avenue West and Superior Street, Miles leased space and became the proprietor of the hotel’s Barber Shop and Bath Rooms. The Duluth newspaper called the shop, which was to open in a few weeks, “the best shop, without an exception, in the state of Minnesota.” When the shop opened in the fall, Miles took an ad in the Duluth Daily Tribune that announced the “Only Bath Rooms in Duluth.”

Alexander Miles respectfully announces that in connection with his superb Tonsorial Parlors in the St. Louis hotel he has fitted up as fine a set of bath rooms as can be found this side of Chicago, and where his patrons can have either hot or cold baths at any hour of the day or evening, and on Sunday forenoons. . . . Having been at a heavy expense in fitting up bath rooms unexcelled by any others in the Northwest, I am sure that those who try my baths once will be disposed to come again. (Duluth Daily Tribune, Oct.14, 1882, p.3)

In June of 1883, Miles applied for a second patent, this for a formula for an improved hair dressing or hair tonic. It’s unclear if this is the formula for Tunisian Hair Dressing that he sold in Winona. He was granted the patent in December of 1883.

Miles built a home on Duluth’s hillside at 311 W. Fourth St. He had purchased the entire eastern half of the block of the upper side of West Fourth Street between Third and Fourth avenues west. Later he would add a barn for his horses and carriage.

Miles also invested heavily in real estate, a good prospect at that time in the rapidly

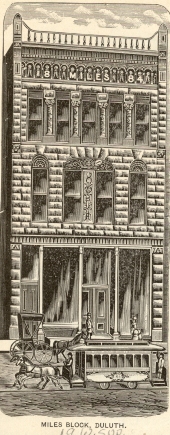

Duluth Journal of Commerce Co.1886

growing city. In 1883, he began planning construction of the Miles Block, a three-story brick office building at 19 W. Superior St. The building was designed by the notable Duluth architectural firm of Oliver Traphagen and George Wirth. J.M. Quimby & Sons cut the granite for the building’s cornerstones and front steps from their stone works on West Superior Street. In July of 1884, the Duluth newspaper further reported on the building’s progress:

Four cylindrical columns of Vermont granite, five feet long and nine inches in diameter, have arrived for the third story front of A. Miles’ block. They are by far the finest stones yet used in this city. The cornice and sky light for this block have also arrived. (Duluth News Tribune, July 24, 1884, p.1)

The newspaper reported that the retail space on the first floor would be ready for occupancy by the middle of August, 1884.

In May of 1887, Miles applied for a patent, simply titled “Elevators,” for making the operating of elevator doors safer. Why Miles, with all his other interests at the time, focused on elevator doors is puzzling. An article in the Duluth newspaper in October of 1887 says Miles had been thinking of the invention for some years but had begun the construction of a model about eight months previously. A look at the layout of the main floor of the St. Louis Hotel, however, might give a clue. Miles’ barber shop was located next to the elevator, even sharing a wall. It’s only speculation, but it’s easy to imagine Miles, while at

Duluth Daily Tribune, April 12,1882

work, hearing the operation of the elevator and thinking of ways to improve it. Miles’ patent aims to improve elevator door safety in two ways: to automatically block the elevator’s wall opening when the elevator car is not on that floor, and to automatically open the cage doors when the elevator reaches a floor and close the doors when the elevator car is moving. Miles’ idea for blocking the opening when the car was not present was to use a canvas or woven-wire curtain that would move up and down at the appropriate times. In the January 2016 issue of Elevator World, Dr. Lee Gray points out that the curtain would present other safety concerns, such as passengers getting their hands or fingers caught in the moving curtain. The second idea, the opening and closing of doors, seems to be workable, according to Dr. Gray. He also points, out, though, that Miles’ system is not fully automatic because it required an operator to manipulate a foot pedal to start the doors opening or closing. It’s unclear whether Miles ever sold the rights to this patent.

In 1887, a reporter from the Western Appeal, a weekly newspaper published in St. Paul, MN, that was aimed at the growing educated black population in the Midwest, visited Miles in Duluth. Miles was chosen for a story partly because he was the wealthiest black man in Minnesota. After breakfast, Miles took the reporter on a carriage ride around the city:

The city is beautifully situated, and has grown most rapidly within the past few years, and to-day real estate is more valuable than in most parts of St. Paul. In the afternoon, Mr. Miles took us behind his black roadster Harry G, and showed us the suburbs for miles around. Mr. Miles is particularly proud of his horses, which are as fine as any in the city, particularly Harry G. (Winona Daily Republican, Nov. 10, 1887, p.3)

The reporter described Miles’s home as “a very comfortable residence on an excellent lot overlooking the lake . . . in a style in accord with his means.”

In July of 1888, Miles sold his barber shop and bath rooms in the St. Louis Hotel to two barbers, William H. Gwathmey and a man named Harris. Miles would focus his efforts on real estate, and open an office in the Miles Block.

For the next few years, Miles concentrated on buying and selling real estate, managing his properties, and working to get streets and alleys improved around his properties. In the summer and fall of 1890, Candace and daughter Grace took a three-month trip to Iowa, Illinois, and other states to visit friends, but Miles didn’t go. He did, however, frequently travel to the Twin Cities on business trips.

In the early 1890s, Miles began planning for construction of a series of homes on his property on West Fourth Street. He again hired the architectural firm of Oliver Traphagen, now with partner Francis Fitzpatrick, to design the homes. Construction of the late Queen Anne-style homes began in January of 1892, and he began advertising them for rent in June of that year. When completed, there were six homes on West Fourth Street—with addresses from 301 to 311—and six homes (two of which were duplexes) on Piedmont Avenue East. Miles and his family lived in the home at 312 Piedmont Ave. E. and the rest were rented out. Piedmont Avenue East was renamed Mesaba Avenue about 1893. Five of the six houses on West Fourth Street remain standing today. Of the buildings on Piedmont Avenue East, only one remains—the house that Miles lived in. That address is now 450 Mesaba Ave.

Shortly after Miles’ building project, the U.S. entered a period of economic recession, begun with the Panic of 1893. While the unemployment rate wasn’t measured directly at the time, modern estimates indicate it grew from three or four percent in 1892 to ten or eleven percent nationally in 1893; and it remained in double figures through 1898. Eventually, property values plunged, and Miles had trouble paying off his loans and taxes. And there was not much of a market for property. Miles, once estimated to be worth about $500,000, began to see his wealth depreciate.

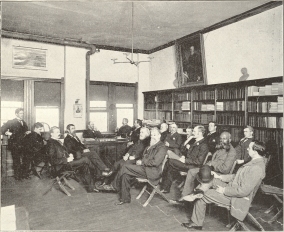

During the decade of the 1890s, Miles was active in the political and business affairs of

Duluth Chamber of Commerce, 1895

Duluth and a leader in the black community. He was at the time the only black member of the Duluth Chamber of Commerce. On February 12, 1896, Miles served as chairman of Duluth’s first official celebration of the birthday of Abraham Lincoln. The Minnesota Legislature had just made the day a legal holiday in the 1895 legislative session. The event was sponsored by Zenith City Lodge No. 14, Colored Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization of which Miles was a member. The program was held at the old Odd Fellows Hall at 20 N. Lake Ave. In his remarks, Miles said:

Words are inadequate to express my appreciation of the honor of acting as chairman upon so important an occasion as this meeting which aims to do honor to the patriot and martyr, Abraham Lincoln. . . .let us remember that through the eternal years, so long as virtue, honesty, heroism and sacrifice are respected, so long will the influence of Abraham Lincoln live, and so long will his name be honored and revered. (Duluth News Tribune, Feb. 13, 1896, p. 5)

Two black attorneys and orators from the Twin Cities, J. Frank Wheaton and Frederick L. McGee, were the main speakers at the celebration. Mayor Ray T. Lewis and Mayor-elect Henry Truelson also attended and spoke.

In March of 1896, Miles chaired a meeting at St. Mark’s A.M.E. Church in Duluth for all black citizens of St. Louis County to discuss “forming a permanent organization for the advancement of the interests of the people.”

Later in 1896 he was named chairman of the Colored Republican Club of Duluth and president of the Federation of Colored Men of St. Louis County. In that last role, he called a meeting in Duluth on June 9, 1896, to discuss a recent decision of the hotel and restaurant owners in St. Louis, Missouri, to deny services to black people in town for the Republican National Convention later in the month. Miles was to be one of two black men representing Minnesota to meet with representatives at the convention. Speaking at the meeting, Miles said:

I think it is time that the nation should awaken to the fact that the negro is a citizen and not a pest. . . . I had intended going to St. Louis to counsel with the leading men of my race on the existing conditions of affairs, but since they have declared that a negro must not expect to be treated as a man and a citizen, I cannot consistently go, after enjoying all the rights and privileges of any other citizen of the state of Minnesota. (Duluth Evening Herald, June 9, 1896, p.6)

In the late 1890s, Miles began selling his Duluth properties to pay off back taxes and mortgages. He sold the Miles Block in 1901 to the Zenith Investment Company for $28,000. Zenith sold it in 1907 for $50,000, and it was demolished in 1910. For two years, he had been working with another Duluthian, Mason H. Seely, on the idea of forming a fraternal benefit society specializing in providing life insurance for black people. It was an accepted fact at the time none of the 227 fraternal benefit societies in the U.S. would sell insurance to minorities because, it was claimed, their mortality rate was so high. Miles and Seely researched the claim and found that black people had a lower mortality rate than any other race of people. They moved their families to Chicago in 1899 and founded the United Brotherhood fraternal insurance society to make insurance coverage available to everyone, regardless of race, religion, or politics. The founding of United Brotherhood was announced on Sunday, January 14, 1900, at a Chicago church. Miles spoke at the ceremony, saying,”This is a fraternal, charitable and beneficial society, organized for the promotion of the welfare, social and fraternal, of its members and the protection of those dependent upon them.”

Black leader Booker T. Washington was the main speaker at the event. He had just arrived from Tuskegee, Alabama. He stated, in part:

I believe that this organization is a stepping stone to higher conditions. It is in line with my efforts for the last seventeen years. It puts people in habits of thrift and economy and in a spirit of good citizenship. And I want to say in regard to this order that it is better to have business men in it. You don’t want orators to do business for you. You must have business men. (The Appeal, St. Paul, MN, Jan. 20, 1900, p.4)

Miles was named president (also called imperial regent) of the organization and Seely was the secretary. Among the officers was J. Frank Wheaton, the Twin Cities attorney who had spoken with Miles at the 1896 Lincoln’s birthday celebration in Duluth. He was now a member of the Minnesota Legislature. In December of 1900, Miles was replaced as president with the election of Dr. Daniel H. Williams, one of the original officers.

Alexander and Candace, now in their middle 60s and having lost most of their money, moved to Seattle, Washington. There, they rented a downtown apartment and Miles took up his old trade as a barber in the Hotel St. Francis, a residential hotel. Candace died of heart disease on November 4, 1905. Following her death, Miles moved into a rooming house a few blocks from the hotel.

In 1907, a Seattle Daily Times reporter, upon discovering that Miles had once been a wealthy man and had lost his fortune, interviewed him and wrote a story about his life. Miles described his life upon moving to Duluth:

I started in at my trade, and gradually built it up until I had an establishment of my own of goodly size. I piled up my money, little by little, and invested it carefully in real estate, getting as much down-town property as I could. By and by things began to move more rapidly, and, after years of waiting, I found my property becoming of value, while Eastern investors were putting fortunes into Duluth. . . . Well, at last the bubble burst, and property that was worth fortunes declined in market value to a song. Rents amounting to hundreds and hundreds of dollars a month declined to almost nothing. To meet my obligations it was necessary to sacrifice my property. . . (Seattle Daily Times, Nov. 3, 1907, p.35)

Miles told the reporter that the greatest loss to him was losing his wife, Candace, a couple of years earlier.

Miles continued to work as a barber in Seattle until he became seriously ill in 1918. In May, Cayton’s Weekly, a local African-American newspaper, printed a note that he was being cared for by his many friends. It mentioned his one-time wealth and that after financial failure he had moved to Seattle but that “he has only been able to keep the wolf from the door and dream of seeing better days.” Miles died on May 7, 1918. The next issue of Cayton’s Weekly ran another story about him, describing his life and his death:

Sickness overtook him and the end seemed to be in sight, but his old time ambition was still alive and he refused to bow to the inevitable. Being without sufficient funds to be cared for at a private sanitarium the county hospital was suggested, at which his whole soul rebelled, but friends found it necessary to take him there. He died the next day. . . (Cayton’s Weekly, Seattle, WA, May 11, 1918, p.4)

Two days later, his body was cremated.

In Duluth, not much remains of Alexander Miles’ life, except for five of the six rental

Homes at 307,305,303, and 301 W. Fourth St.

homes he had built on West Fourth Street. Over 120 years old, they are in need of some restoration and most have been covered with aluminum siding, but they still have a distinctive look.

Pingback: Alexander Miles: Barber, real estate investor, inventor - Perfect Duluth Day

Reblogged this on vetiver.