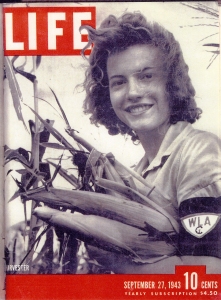

As World War II continued into 1943, some U.S. industries were experiencing shortages of workers. In Minnesota, the pinch was felt especially acutely in agriculture, food processing, and logging. Women and even children often stepped up to help with the labor shortage in agriculture and food processing. One notable local example was  17-year-old Duluthian Shirley Armstrong, who appeared on the cover of the September 27, 1943, issue of Life magazine because she was working in corn fields near Fairmont, Minnesota. She and several other young women from Duluth were featured in an article about the Women’s Land Army.

17-year-old Duluthian Shirley Armstrong, who appeared on the cover of the September 27, 1943, issue of Life magazine because she was working in corn fields near Fairmont, Minnesota. She and several other young women from Duluth were featured in an article about the Women’s Land Army.

In spite of the help, the labor shortage grew worse. Early in 1943, the state of Minnesota had begun working on a plan for using prisoners of war to fill some vacant jobs and help keep the industries operating smoothly and able to provide the country with needed food and lumber. A small number of prisoners were used in Minnesota agriculture in 1943, but usage increased greatly in 1944.

In a meeting held on November 11, 1943, in the St. Louis County Courthouse in Duluth, U.S. Army representatives made a presentation to a group of timber producers outlining the procedures for employing prisoners of war. At that time, no prisoners of war had been used in the lumber industry in Minnesota. According to an article in the Duluth Herald, the timber producers were told:

Prisoner of war labor is last resort labor. . .In order to obtain such aid to production an employer is required to obtain a certificate of necessity from the War Manpower commission. Such certification is on the premise that no other labor is available through usual channels. (Duluth Herald, November 11, 1943, p.1)

By the end of November, a representative of Timber Workers’ Union, Local No. 29, covering northern Minnesota, protested the use of prisoners in the industry. In a telegram to Army officials, Ilmar Koivunen said, “use of war prisoners in Minnesota timber operations bitterly resented by timber workers. It can only lead to widespread dissatisfaction” (Duluth Herald, November 30, 1943, p.1). Two weeks later, the Mayor of Duluth, Edward H. Hatch, publicly opposed the use of prisoners of war to help the logging industry.

But the industry proceeded with the plan, and by early 1944 a former Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp near Remer in Cass County, about 115 miles northwest of Duluth, had been approved by the Army to house prisoners. A group of German prisoners on their way to Remer, along with their Army guards, arrived on the Soo Line railroad in Duluth on January 30, 1944, to spend the night in the depot on Sixth Avenue West and Superior Street. They had been sent from a major prisoner-of-war camp in Concordia, Kansas. The next day they continued by train to the Remer site to begin nine days of upgrading work, making the camp ready to house prisoners who would be harvesting pulpwood to help alleviate the serious shortage.

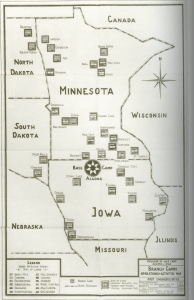

The camp at Remer was the first in Minnesota to use German prisoners to cut pulpwood and was considered a test case. Eventually there would be four such camps in Northeastern Minnesota: one near the town of Bena in Cass County; one 23 miles north of Deer River in Itasca County, also called the Cut Foot Sioux Camp; and one 22 miles north of Grand Rapids which opened in early 1945 when the Remer camp closed and operated for only four months. By June of 1944, oversight of camps in Minnesota, Iowa, and North and South Dakota was assigned to a base camp near the town of Algona, in north central Iowa. Officials at Algona would be responsible for 34 camps, 20 of which were located in Minnesota.

County; one 23 miles north of Deer River in Itasca County, also called the Cut Foot Sioux Camp; and one 22 miles north of Grand Rapids which opened in early 1945 when the Remer camp closed and operated for only four months. By June of 1944, oversight of camps in Minnesota, Iowa, and North and South Dakota was assigned to a base camp near the town of Algona, in north central Iowa. Officials at Algona would be responsible for 34 camps, 20 of which were located in Minnesota.

In April of 1944, the Duluth News Tribune described the Remer Camp in a lengthy article in its Sunday Cosmopolitan section (Duluth News Tribune, April 16, 1944, Cosmopolitan pp. 1, 6-7). The reporter, who had visited the Remer facility on March 6, said the camp housed several hundred German prisoners, most of whom had served in the Afrika Korps under Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. The article says most of the prisoners had arrived by rail and had traveled through Duluth. The prisoners were paid ten cents a day by the federal government, and, on days they worked, another 80 cents a day from the company benefiting from the work; the pay was in money negotiable only at the camp canteen, where prisoners could purchase items such as cigarettes, candy, razor blades, and soap. When asked by the reporter about the prisoners’ attitudes, Capt. Richard D. Harding, camp commander, said:

They are courteous, well-disciplined as soldiers and have the utmost respect for American officers. They never fail to salute, they obey orders without hesitation and observe military regulations and camp rules to the letter.

A May of 1944 Duluth News Tribune article describes what was probably a typical Duluth stopover for prisoners heading by train from Iowa to the Northeastern Minnesota camps (Duluth News Tribune, May 18, 1944, p.1):

Another group of Nazi prisoners passed through Duluth late yesterday under heavily armed guard, en route to a northern Minnesota lumber camp. Chatting gaily among themselves as they strode from their prison train in the Soo Line depot, they were marched down the lower sidewalk of West Superior Street and filed through the doors of a cafeteria to be fed.

They had dinner at Miller’s Cafeteria, 318-320 West Superior Street, and according to the article were seated in the

upper level, where they would be separated from the other diners. After an hour, they were marched back to the Soo Line Depot by going down Fourth Avenue West and then west along Michigan Street. Crowds lined the sidewalk to observe the prisoners, according to the article, and most were silent except for “an elderly woman [who] wept openly as she watched the Nazis file past her.”

The four northern Minnesota camps were closed during 1945; the last to close was the camp at Deer River. Its last official day of operation was December 26, 1945.

If you’d like to learn more about the prisoner-of-war camps in Minnesota during World War II, check out the book Swords Into Plowshares, by Dean B. Simmons, from the Duluth Public Library.

Pingback: German Prisoners of War in Northeastern Minnesota - Perfect Duluth Day

my dad was taken to a camp in minnesota.I don;t know witch camp it was .His name was karl Nendsa and he would tell us stories of working in the fields and some of them could even go for a beer in a nearby town. They were treated very nice. When dad was released he went north into Canada where all our family is today.. I;m wondering if there is a list of all german prisoners of war with my dads name on it.

Hans,

I wrote this article. In researching it, I didn’t see any mention of lists of names of German prisoners. But I think most of the prisoners that ended up working in camps in Minnesota came through Camp Algona in Iowa. There’s a museum there commemorating the camp, so you might try contacting them to see if they have any information. The email is campalgonapowmuseum@gmail.com

David Ouse

thanks for the help david. I will look into this new information. Will keep you informed/ Hans Nendsa

I worked with a Karl Nendsa at the Avoca Mines, Ireland. He had been a prisoner of war in Canada. I may have some information for you if you wsh to contact me.

I knew a Karl Nendsa that had been a POW in Manitoba, Canada. I worked with him in Ireland at the Avoca Mines.

My friend (half Norwegian / half German) had a grandfather that was captured in North Africa (Tripoli) after the failed North African campaign. He was kept in the U.S. until 52/53 before being released back to Germany.

He was in Cut Foot Sioux as long as they kept it open.